|

|

|

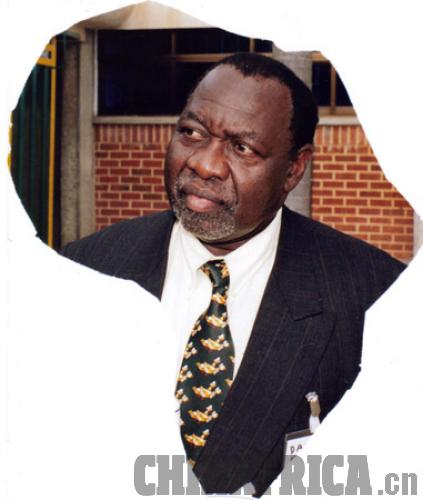

David Kakaya, Professor of International Relations and Director of the Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs at the United States International University, Nairobi, Kenya |

This year the African Union (AU) will mark the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), a precursor of the current organization, on May 25, 1963. The OAU embodied a collective spirit that brought together 32 governments to sign the OAU Charter in Addis Ababa. This spirit has since spread, and the AU's membership now includes 54 countries.

Africa has made commendable strides, both economically and politically, while facing some formidable problems. This progress was made possible by integration at both the regional and continental levels, which allowed cross-border development programs to facilitate the upgrading of economies of scale.

Even prior to the formation of the OAU, it was clear that integration was a process and not an event. The inspiration to continue the process of integration in Africa by founding the OAU came from outside the continent. One source of inspiration was the Bandung Conference of April 1955, where 29 governments of African, Middle Eastern and Asian countries gathered together. Pan-Africanists who attended this conference returned home with new ideas to foster greater integration in Africa.

Africa's foremost Pan-Africanist, Ghana's first President Kwame Nkrumah, best summed up the continent's future: "Here is a challenge which destiny has thrown out to the leaders of Africa. It is for us to grasp that golden opportunity to prove that the genius of African people can surmount the separatist tendencies in sovereign nationhood by coming together speedily, for the sake of Africa's greater glory and infinite well-being, into a Union of African States."

The OAU made significant strides in integration, and the AU is now continuing this work with a regional approach, instituting strategies that focus less on politics and more on socioeconomic issues. This regional integration approach involves several groupings. In West Africa, there is the Economic Community of West African States, with a conflict intervention force, the Economic Community of West African States Monitoring Group. The Horn of Africa is integrated through the Intergovernmental Authority on Development.

The East African Community has expanded from the three countries of Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania to include Rwanda and Burundi. South Sudan and Somalia have applied to join this group. In Central African countries, integration is centered around francophone nations. These include the Central African Republic and Gabon. Most North African countries are members of the Maghreb Union as well as the predominantly Middle Eastern Arab League.

Further south, the Southern African Development Community member countries are connected by a customs union for the promotion of trade. Integration has been enhanced by membership in the Indian Ocean Rim Association for Regional Cooperation. The primary purpose of this association is to ensure the sustainable utilization of the Indian Ocean resources.

The current challenges to Africa's integration are both natural and man-made. Natural challenges include drought, floods and diseases, like HIV/AIDS and malaria. Man-made difficulties cross over political, social and economic lines. Political challenges include democratization, human rights, implementing the rule of law and armed conflicts. Social challenges consist of brain drain, illiteracy, poverty and corruption, while economic challenges revolve around heavy debt burdens, marginalization, insufficient foreign investment, trade inequalities and a high population growth rate.

Despite these obstacles, African integration can help the continent secure a place and voice on the global stage. In the words of Ghanaian Kingsley Amoako, former UN Under Secretary General, "Unity will not make us rich, but it can make it difficult for Africa and the African peoples to be disregarded and humiliated." |