|

|

|

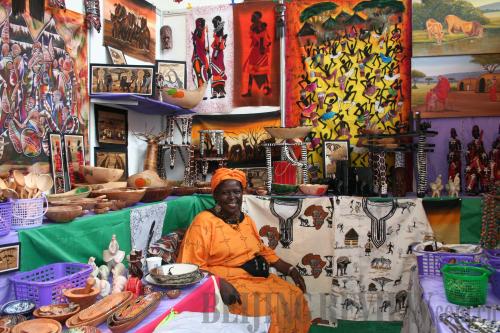

CROSSING BORDERS: The EAC common market is keeping small and large business in East Africa to develop (XINHUA) |

As the clock ticked toward midnight on June 30, 2010, the mood in Nairobi, Kenya's capital, and in the rest of East African Community (EAC), was expectant. The region's vibrant media had already set the stage: the East Africa Community Common Market was here.

Kenya's President Mwai Kibaki and his minister in charge of EAC affairs, Amason Kingi, were at the Kenyatta International Conference Center - a government-owned state-of-the-art meeting facility - to publicly declare their support for the Common Market.

Their message to the expectant public was that the borders were now open - to people, goods, money and services.

To Kenya's president, the Common Market was "the boldest step" as the region looked forward to the mirage that has been a political federation. His statement takes note of the tumultuous launch of the Customs Union – to allow goods to move across the borders duty-free - five years ago. The regimes in the then three member countries - Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania - successfully sorted out the teething problems in the cross-border tariffs.

With this, Rwanda and Burundi, the two nations that were smarting from a history of conflict and genocide, joined the community to boost their economies. The two are landlocked and with their alternative access to imports being the conflict-ridden Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya and Tanzania were automatic gateways.

Thus Rwanda and Burundi were duly taken in, expanding the EAC membership to five. This gave the bloc the economic stamina it needed, with a huge market of 126 million people and a GDP of $73 billion.

To Kenya's president, the Common Market "will open up employment opportunities, avail greater opportunities for trade in goods and services and provide opportunities for greater capital mobilization to boost investment in the region."

Kenya's Nairobi is the de facto capital of the region, it being a hub for business and diplomacy. It houses dozens of international organizations, including the United Nations.

Every president in the region - Tanzania's Jakaya Kikwete, Uganda's Yoweri Museveni, Rwanda's Paul Kagame, Burundi's Pierre Nkurunziza and Kenya's Kibaki - must have agreed that these advantages were mutual and that's why they appended their signatures of the Common Market Protocol back in November 2009 at a high-profile event in Arusha, Tanzania.

Kingi, Kenya's EAC Minister, agrees: "In an increasingly globalized world, you cannot go it alone; we need a united region to develop our competitive advantage."

"This can only be achieved by removing restrictions on the factors of production, so as to increase efficiency in our markets and promote economic growth and cooperating in infrastructure such as transport and energy supply to make the region more attractive to both foreign and domestic investments," the minister said on that eve of July 1, the effective date for the Common Market roll-out.

But to the technocrats charged with the implementation of the protocol, the "complex and long march" has just begun.

|