|

|

|

A DAY IN THE LIFE: time to unwind (XINHUA) |

Summer in Yuncheng, Shanxi Province is hot and humid. Li Xianlei, a forklift truck driver at a coal mining company has just come back from working the night shift. Born in the late '80s in Henan Province, the 23-year-old has been a migrant worker for six years. "After graduating from high school, I left my hometown and have been working as a forklift truck driver in cities ever since," Li explains.

Just like Li, many young people in rural areas these days leave to find work in China's metropolises. Most of them are born after 1980, holding an agricultural hukou (a crucial household registration document), but working in non-agricultural sectors. In January 2010, the first mention of the phrase "new generation of migrant workers" appeared in the Chinese government's No. 1 Document, urging the adoption of targeted measures to help the group. According to data released by the National Bureau of Statistics of China, in the year 2009, migrant workers between the ages of 16 and 30 accounted for over 61.6 percent of the overall migrant workforce (which numbers 145.33 million). As a unique demographic, these young migrant workers are garnering much public attention.

|

|

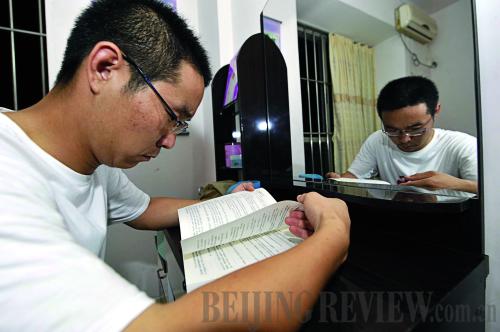

A DAY IN THE LIFE: hitting the books (XINHUA) |

"We are different"

In Mandarin, migrant worker translates as "nong min gong." The phrase is a combination of first "farmer" and then "worker." Li doesn't like its implied definition. "It seems to mean that although you're a worker in big cities, you're first and foremost a farmer. But as a matter of fact, I can't farm at all," he says. "Migrant workers of my father's generation are both farmers and workers. My father, he is a farmer, but he also went looking for work when farms were not that busy. We are different."

Indeed, the new generation of migrant workers is much different from their fathers' generation. According to the Report on the New Generation of Migrant Workers released by the All China Federation of Trade Unions this past June, these new migrant workers are more like their urban peers. Many migrated to the city with their parents as children, or are more familiar with urban life, having left their hometowns after completing junior or senior high school. The survey shows that 89.4 percent of this new generation are unable to farm, and 37.9 percent of this number have no farming experience at all. Compared to older generations, the post-80s demographic worries less about basic living necessities like food and clothes. They don't work simply to make a living. Equality, respect, sense of belonging and recognition from others are considered important aspects of life.

Unlike their fathers' generation, relatively ambivalent about working conditions, today's young migrant workers have their own criteria when it comes to selecting jobs. "Salary is the most determinant factor, but working environment is also very important. I wouldn't choose [work that is] too dirty and overloaded," says Li. Two months ago, before he came to Yuncheng, he traveled to Beijing for a job interview. It went successfully, but he turned down the offer. "Originally I planned to work in Beijing, but it was so hot there. It's terrible to drive a forklift truck in such weather. Besides, the salary was quite low," he explains.

But for Li, work is not merely about money. It's also an opportunity to visit many places. "I've worked in many cities in China, such as Beijing, Tianjin and Zhengzhou, Xinyang, Xuchang in Henan Province, Yichang in Hubei Province, Chengdu in Sichuan Province, and Ganzhou in Jiangxi Province," he says proudly.

Lin Juan (not her real name), a 22-year-old from Sichuan, feels differently. For her, improving her skill set is more important. Working in a hair salon in Beijing, Lin is responsible for washing customers' hair. "The salary here is low. But besides washing hair, I'm also learning basic perming and coloring. The boss treats me well. I believe I'll make more money as I become more skillful," she says.

|