|

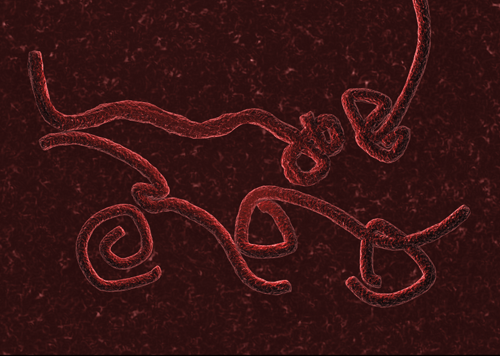

This summer marked the fourth Ebola outbreak in Uganda since 2000. The Ebola virus, which was discovered in the Republic of Congo in 1976, is known for hemorrhagic fevers that rapidly and violently wreak havoc on the human body. By the time Uganda's Ministry of Health (MOH) declared in August the outbreak "under control," 16 people had died from exposure.

It could have been worse. "This is a small, small outbreak in the corner of Uganda," says Dr. John Kinsman, of the outbreak that occurred in Kibaale, a district in the western reaches of the country. Kinsman is a public health researcher who has tracked outbreaks of the filovirus in Uganda since 2000. "It's very important that people are aware of it. But in the region, 1,500 - maybe 1,600 - people have died from Ebola over a period of 40 years. That many people die of HIV every week in South Africa," he notes. "The relative importance of Ebola as a sort of global health problem is very low and yet the relative degree of panic it gets is very, very high."

This reaction may be in part due to the virus' elusiveness. Ebola has no cure, and its natural reservoir - the creature that hosts the pathogen between outbreaks - is unknown to scientists. Many believe that bats may be carriers for the virus, but research into this possibility is limited. "They're not easy animals to catch," explains Dr. Daniel Bausch, an American epidemiologist who specializes in tracking emerging infectious diseases. "Even when you do find bats that may be infected, the number tends to be small. If you have thousands of bats, it's not going to be hundreds that are going to be infected, it might just be a few."

Bausch and Kinsman both worked in Uganda during the country's largest Ebola outbreak, which lasted from September 2000 to February 2001. Bausch, stationed in field hospitals as a primary response person, struggled to find nonexistent solutions: "There really aren't any effective drugs at all," he says. "One of the hard parts about treatment is that everything happens so fast. By the time you get a patient who's very sick and they come to the hospital, the time from when they first fall ill to death is only an average of 8 days. We still don't have the antivirals that we need to really get someone better once they get sick."

In spite of these gaps, scientists do know there are five different strains of the virus. Each has its own fatality rate, ranging anywhere from 90 to 0 percent mortality in humans. The strain that appeared Uganda this summer - Ebola-Sudan - kills about 55 percent of those infected. Still, when the 2000 outbreak hit, Uganda's national Virus Research Institute (UVRI) was unable to perform the nucleic acid sequencing needed to identify the strain they were dealing with.

"UVRI didn't have actually have facilities for Ebola because it's such a dangerous virus," explains Kinsman, who was living in Uganda in 2000, and whose paper on responses to the outbreak was published in the journal Globalization and Health this past June. "They had to ship samples to the [National] Institute of Virology in South Africa and they confirmed it was Ebola there."

Kinsman is quick to point out that "an outbreak in Uganda, as things stand today, is likely to be pretty well-controlled." Since 2000, UVRI's capacity to deal with Ebola has boomed. The first cases of Ebola reported in July were discovered and analyzed at UVRI's lab in Entebbe, allowing for better containment and tracking of the virus, and a way to anticipate just how devastating the pathogen's impact might be within Uganda's borders. "The most important thing for emerging diseases is local capacity," says Bausch.

Kinsman would like to see other emerging diseases benefit from Uganda's improved capacity. The north of the country has also been crippled by an ongoing epidemic of nodding disease in 3,000 children, according to Ugandan data. The disease, though deadly, does not appear to be infectious.

Uganda's Ministry of Health has access to $1 million in emergency funds to address the Ebola outbreak, according to ministry representatives. Its requests for funding to deal with nodding disease have not been as well received by the country's Ministry of Finance. In Kinsman's view, nodding disease is losing against the power of perception. "It's not seen as a threat to anybody outside those specific areas, and Ebola is," he said. |